Beatles In Colour → George Harrison In ORANGE & YELLOW For @radgeorgie

Beatles in Colour → George Harrison in ORANGE & YELLOW For @radgeorgie

More Posts from Calabrie and Others

George Harrison visiting Bob Dylan in Woodstock, New York (Nov. 1968)

I heard someone walk into the room and, assuming it was Barry Imhoff or Gary Shafner, I kept pounding away at the keys of the electric typewriter.

“Hi,” Bob Dylan said, pulling a chair over to my desk and slumping into it. “So have you seen George lately?”

Startled by his voice, it took a few seconds for me to respond. “Not since his tour a year ago,” I said.

“I really like George,” he said, reaching into his jacket and pulling out a cigarette.

I nodded my head. I liked George, too.

“So, I was thinking about it. I remember you from the Isle of Wight.” He turned his head and smiled at me, sideways. “I can’t believe I forgot my harmonicas. That was cool when you flew in on the helicopter.”

“Yeah, that was pretty cool,” I agreed. I wasn’t really sure how to talk to Bob, so I just followed his lead.

“That was a weird show,” he said. “I hadn’t performed in a long time, and I was pretty nervous.”

“You didn’t seem nervous,” I said, hoping to reassure him.

“Yeah?” he turned his head to the side and looked at me, narrowing his eyes, measuring my honesty. Then he seemed to relax. “Well, that’s good. But I sure felt it.”

He laughed, then, almost shyly, and averted his eyes. “I’m glad you’re on the tour,” he said. “Any friend of George’s is a friend of mine.”

- Chris O’Dell, “Santana (September - October 1975)”, Miss O’Dell: My Hard Days and Long Nights with The Beatles, The Stones, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and the Women They Loved

Paul's grief over time: A Compilation

“During the session [in 1981] Paul fell into a lugubrious mood. He said, ‘I’ve just realized that John is gone. John’s gone. He’s dead and he is not coming back.’ And he looked completely dismayed, like shocked at something that had just hit him. ‘Well, it’s been a few weeks now.’ He said, ‘I know, Eric, but I’ve just realized." (Eric Stewart)

“It’s still weird even to say, ‘before he died’. I still can’t come to terms with that. I still don’t believe it. It’s like, you know, those dreams you have, where he’s alive; then you wake up and… 'Oh’.” (Paul, 1986)

"Occasionally, it wells up. Y'know, and I'm at home on the weekend suddenly and I start thinking about him or talking to the kids about him and I can't handle it." (Paul, 1987)

"Is there a record you like to put on just to hear John’s voice?" I ask Paul the next day. Paul looks startled. He fumbles. “Oh, uh. There’s so much of it. I hear it on the car radio when I’m driving.” No, that’s not what I mean", I persist. "Isn’t there a time when you just wish you could talk to John, when you’d like to hear his voice again?" For some reason, he instead responds to the original question.“Oh sure,” he says and looks a little taken aback. ‘Beautiful Boy". (1990)

"Also not obvious is that McCartney [for the Liverpool Oratorio] has penned a gorgeous black-spiritual-like piece for mezzo-soprano that intones the last words spoken to John Lennon as he lay dying of gunshot wounds in the back of a New York police car -- "Do you know who you are?" McCartney gets a bit choked up at one point when he reveals, "Not a day goes by when I don't think of John.” (1991)

"Delicious boy, delicious broth of a boy. He was a lovely guy, you know. And it gets sadder and sadder to be saying “was”. Nearer to when he died I couldn’t believe I was saying “was”, but now I do believe I’m saying “was”. I’ve resisted it. I’ve tried to pretend he didn’t get killed." (Paul, 1995)

"Paul talked about John a a lot, but the strange thing was that it was in the present tense, “John says this" or "John thinks that. Very weird." (Peter Cox, 2006)

“John Lennon was shot dead in 1980. That totally knocked dad for six. I haven’t really spoken to him a lot about it because it is such a touchy subject." (James McCartney, 2013)

"It's very difficult for me and I, occasionally, will have thoughts and sort of say: "I don't know why I don't just break down crying every day? […] You know, I don't know how I would have dealt with it because I don't think I've dealt with it very well. In a way… I wouldn't be surprised if a psychiatrist would sort of find out that I'm slightly in denial, because it's too much." (Paul, 2020)

"Like any bereavement, the only way out is to remember how good it was with John. Because I can't get over the senseless act. I can't think about it. I'm sure it's some form of denial. But denial is the only way that I can deal with it." (Paul, 2020)

"When I talked to Paul about John and when he missed John most, he couldn't answer me for a long time and his eyes teared up. And I asked him where he thinks about John and when John comes into his mind and he just … he lost it, he completely lost it." (Bob Spitz, 2021)

-------------------------------------------------

The following two are from the gossip website Datalounge, so they may or may not be true. Still interesting though:

"The one time I was ever actually in a room with Paul, zillion people between me and him (and no way I'm gonna bother him, all of us who travel in celeb circles have people we're fans of and all of us inexplicably try to hide it to seem "cooler"), he started talking loudly about himself and John, and how hard it was not to have him there. I remember him saying something along the lines of not a day passing that John's not still in it with him, but it's not like he can pick up a phone and say, "Hey, just needed to hear your voice today," and even when he got craggy responses, he still missed them. He misses it all, and it's bothering to him that he misses him more as time goes on -- it doesn't heal, he just learns new ways to bandage the wound."

“Since everyone is anonymous here, I guess I can give a bit of info I got from a female friend of mine who at one time worked as one of Paul’s assistants. [...] She does not know for certain if John and Paul were involved but she suspects it since to this day whenever John’s name is brought up he acts in her words ‘like a widow’ and he also addresses John in present tense. He would say things like, ‘John thinks that the music should be like this,’ and during his bitter divorce from Heather he was saying, ‘John says that this is getting nasty.’ Kind of creepy." (this one actually seems very intriguing because it sounds very similar to what Peter Cox said, about Paul often talking about John in the present tense, saying "John says.." or "John thinks...")

Thelma Pickles, John Lennon’s first girlfriend at Liverpool College of Art, on her relationship with John

My first impression of John was that he was a smartarse. I was 16; a friend introduced us at Liverpool College of Art when we were waiting to register. There was a radio host at the time called Wilfred Pickles whose catchphrase was "Give them the money, Mabel!". When John heard my name he asked "Any relation to Wilfred?", which I was sick of hearing. Then a girl breezed in and said, "Hey John, I hear your mother's dead", and I felt absolutely sick. He didn't flinch, he simply replied, "Yeah". "It was a policeman that knocked her down, wasn't it?" Again he didn't react, he just said, "That's right, yeah." His mother had been killed two months earlier. I was stunned by his detachment, and impressed that he was brave enough to not break down or show any emotion. Of course, it was all a front. When we were alone together he was really soft, thoughtful and generous-spirited. Clearly his mother's death had disturbed him. We both felt that we'd been dealt a raw deal in our family circumstances, which drew us together. During the first week of college we had a pivotal conversation. I'd assumed that he lived with his dad but he told me, "My dad pissed off when I was a baby." Mine had too – I wasn't a baby, I was 10. It had such a profound effect on me that I would never discuss it with anyone. Nowadays one-parent families are common but then it was something shameful. After that it was like we were two against the world.

I went to his house soon after. It seemed really posh to me, brought up in a council house. We were alone, he showed me round and we had a bit of a kiss and a cuddle in his bedroom. Paul and George came round and we all had beans on toast, then they played their guitars in the kitchen. I had to leave early because Mimi wouldn't allow girls in the house. She was very strict. She wouldn't let him wear drainpipe trousers so he used to put other trousers over the top and remove them after he left the house. We used to take afternoons off to go to a picture-house called the Palais de Luxe where he liked to see horror films. I remember we went to see Elvis in Jailhouse Rock at the Odeon. He didn't take his glasses. We were holding hands and he kept yanking my hand saying, "What's happening now Thel?" John was enormous fun to be with, always witty, even if it was a cruel wit. Any minor frailty in somebody he'd detect with a laser-like homing device. We all thought it was hilarious but it wasn't funny to the recipients. Apart from the first instance, where he mocked my name, I never experienced it until I ended our relationship. We were close until around Easter of the following year, 1959. At an art school dance he took me to a darkened classroom. We went thinking we'd have it to ourselves but it was evident from the din that we weren't alone. I wasn't going to have an intimate soirée with other people present. I refused to stay, and he yanked me back and whacked me one. He had aggressive traits, mainly verbal, but never in private had he ever been aggressive - quite the opposite. Once he'd hit me that was it for me, I wouldn't speak to him. That one violent incident put paid to any closeness we had. I took care to not bump into him for a while. I didn't miss drinking at Ye Cracke with him but I missed the closeness we had. Still, we were friendly enough by the end of the next term. Because he did no work, he was on the brink of failure, so I loaned him some of my work, which I never got back. I've never wondered what might have been. It sounds disingenuous, but I wouldn't like to have been married to John – that would be quite a gargantuan task! He would've been 70 next year and I just cannot imagine a 70-year-old John Lennon. I'd be fearful that the fire would've gone out.

- Interview within Imogen Carter, ‘John Lennon, the boy we knew’, The Guardian (Dec 2009)

Thelma also briefly dated Paul McCartney and later married Mike McCartney’s bandmate, Roger McGough, in 1970.

Thelma also gives more detail of her relationship with John in Ray Coleman's 1984 John Lennon biography. Just to note, she mentions towards the end of the section that their romantic relationship just petered out, and John was never physically violent with her - it's likely the case that by the 2009 Guardian interview above, she would've felt more free to speak about John hitting her as the reason for the relationship's end, rather than this being two contrasting stories.

A year younger than John, Thelma was to figure in one of his most torrid teenage affairs before he met Cynthia. Their friendship blossomed in a spectacular conversation one day as they walked after college to the bus terminus in Castle Street. In no hurry to get home, they sat on the steps of the Queen Victoria monument for a talk. ‘I knew his mother had been killed and asked if his father was alive,’ says Thelma. ‘Again, he said in this very impassive and objective way: “No, he pissed off and left me when I was a baby.” I suddenly felt very nervous and strange. My father had left me when I was ten. Because of that, I had a huge chip on my shoulder. In those days, you never admitted you came from a broken home. You could never discuss it with anybody and people like me, who kept the shame of it secret, developed terrific anxieties. It was such a relief to me when he said that. For the first time, I could say to someone: “Well, so did mine.”’

At first Thelma registered that he didn’t care about his fatherless childhood. ‘As I got to know him, he obviously cared. But what I realised quickly was that he and I had an aggression towards life that stemmed entirely from our messy home lives.’ Their friendship developed, not as a cosy love match but as teenage kids with chips on their shoulders. ‘It was more a case of him carrying my things to the bus stop for me, or going to the cinema together, before we became physically involved.’ John, when she knew him, would have laughed at people who were seen arm in arm.’ It wasn't love's young dream. We had a strong affinity through our backgrounds and we resented the strictures that were placed upon us. We were fighting against the rules of the day. If you were a girl of sixteen like me, you had to wear your beret to school, be home at a certain time, and you couldn't wear make-up. A bloke like John would have trouble wearing skin-tight trousers and generally pleasing himself, especially with his strict aunt. We were always being told what we couldn’t do. He and I had a rebellious streak, so it was awful. We couldn't wait to grow up and tell everyone to get lost. Mimi hated his tight trousers and my mother hated my black stockings. It was a horrible time to be young!’ Lennon's language was ripe and fruity for the 1950s, and so was his wounding tongue. In Ye Cracke, one night after college, John rounded on Thelma in front of several students, and was crushingly rude to her. She forgets exactly what he said, but remembers her blistering attack on him: ‘Don't blame me,’ said Thelma, ‘just because your mother's dead.’ It was something of a turning point. John went quiet, but now he had respect for the girl who would return his own viciousness with a sentence that was equally offensive. ‘Most people stopped short,' says Thelma. ‘They were probably frightened of him, and on occasions there were certainly fights. But with me, he met someone with almost the same background and edge. We got on well, but I wasn't taking any of his verbal cruelty.’

When they were together, though, the affinity was special, with a particular emphasis on sick humour. Thelma says categorically that John and she laughed at afflicted or elderly people ‘as something to mock, a joke’. It was not anything deeply psychological like fear of them, or sympathy, she says. ‘Not to be charitable to ourselves, we both actually disliked these people rather than sympathised,’ says Thelma. ‘Maybe it was related to being artistic and liking things to be aesthetic all the time. But it just wasn't sympathy. I really admired his directness, his ability to verbalise all the things I felt amusing.’ He developed an instinctive ability to mock the weak, for whom he had no patience. He developed an instinctive ability to mock the weak, for whom he had no patience. In the early 1950s, Britain had National Service conscription for men aged eighteen and over who were medically fit. John seized on this as his way of ridiculing many people who were physically afflicted. ‘Ah, you're just trying to get out of the army,’ he jeered at men in wheelchairs being guided down Liverpool's fashionable Bold Street, or ‘How did you lose your legs? Chasing the wife?’ He ran up behind frail old women and made them jump with fright, screaming 'Boo' into their ears. ‘Anyone limping, or crippled or hunchbacked, or deformed in any way, John laughed and ran up to them to make horrible faces. I laughed with him while feeling awful about it,’ says Thelma. ‘If a doddery old person had nearly fallen over because John had screamed at her, we'd be laughing. We knew it shouldn't be done. I was a good audience, but he didn't do it just for my benefit.’ When a gang of art college students went to the cinema, John would shout out, to their horror, ‘Bring on the dancing cripples.’ says Thelma. ‘Perhaps we just hadn’t grown out of it. He would pull the most grotesque faces and try to imitate his victims.’

Often, when he was with her, he would pass Thelma his latest drawings of grotesquely afflicted children with misshapen limbs. The satirical Daily Howl that he had ghoulishly passed around at Quarry Bank School was taken several stages beyond the gentle, prodding humour he doled out against his former school teachers. ‘He was merciless,’ says Thelma Pickles. ‘He had no remorse or sadness for these people. He just thought it was funny.’ He told her he felt bitter about people who had an easy life. ‘I found him magnetic,’ says Thelma, ‘because he mirrored so much of what was inside me, but I was never bold enough to voice.’ Thel, as John called her, became well aware of John's short-sightedness on their regular trips to the cinema. They would ‘sag off’ college in the afternoons to go to the Odeon in London Road or the Palais de Luxe, to see films like Elvis Presley in Jailhouse Rock and King Creole. ‘He’d never pay,’ says Thelma. ‘He never had any money.’ Whether he had his horn-rimmed spectacles with him or not, John would not wear them in the cinema. He told her he didn’t like them for the same reason that he hated deformity in people: wearing specs was a sign of weakness. Just as he did not want to see crutches or wheelchairs without laughing, John wouldn't want to be laughed at. So he very rarely wore his specs, even though the black horn-rimmed style was a copy of his beloved Buddy Holly. ‘So in the cinema we sat near the front and it would be: “What’s happening now, Thel?” “Who’s that, Thel?” He couldn’t follow the film but he wouldn’t put his specs on, even if he had them.’

[...] It was not a big step from cinema visits and mutual mocking of people for John and Thelma to go beyond the drinking sessions in Ye Cracke. ‘It wasn't love’s young dream, but I had no other boyfriends while I was going out with John and as far as I knew he was seeing nobody except me.’ On the nights that John's Aunt Mimi was due to go out for the evening to play bridge, Thelma and John met on a seat in a brick-built shelter on the golf course opposite the house in Menlove Avenue. When the coast was clear and they saw Mimi leaving, they would go into the house. ‘He certainly didn’t have a romantic attitude to sex,’ says Thelma. ‘He used to say that sex was equivalent to a five-mile run, which I’d never heard before. He had a very disparaging attitude to girls who wanted to be involved with him but wouldn’t have sex with him. ‘“They’re edge-of-the-bed virgins,” he said. ‘I said: “What does that mean?” ‘He said: “They get you to the edge of the bed and they’ll not complete the act.” ‘He hated that. So if you weren’t going to go to bed with him, you had to make damned sure you weren’t going to go to the edge of the bed either. If you did, he’d get very angry. ‘If you were prepared to go to his bedroom, which was above the front porch, and start embarking on necking and holding hands, and you weren’t prepared to sleep with him, then he didn’t want to know you. You didn’t do it. It wasn’t worth losing his friendship. So if you said, “No”, then that was OK. He’d then play his guitar or an Everly Brothers record. Or we’d got to the pictures. He would try to persuade you to sleep with him, though. ‘He was no different from any young bloke except that if you led him on and gave the impression you would embark on any kind of sexual activity and then didn’t, he'd be very abusive. It was entirely lust.

[...] Thelma was John’s girlfriend for six months. ‘It just petered out,’ she says. ‘I certainly didn’t end it. He didn’t either. We still stayed part of the same crowd of students. When we were no longer close, he was more vicious to me in company than before. I was equally offensive back. That way you got John’s respect. Her memory of her former boyfriend is of a teenager ‘very warm and thoughtful inside. Part of him was gentle and caring. He was softer and gentler when we were alone than when we were in a crowd. He was never physically violent with me - just verbally aggressive, and he knew how to hurt. There was a fight with him involved once, in the canteen, but he’d been drinking. He wasn’t one to pick a fight. He often enraged someone with his tongue and he’d been on the edge of it, but he loathed physical violence really. He’d be scared. John avoided real trouble.’

- Within Ray Coleman, John Winston Lennon: 1940-66 vol.1 (1984)

Robert Fraser’s interview with Peter Brown and Steven Gaines, All You Need is Love

Some highlights:

Robert Fraser: Peter Asher was Jane’s brother. I think he brought Paul over to my place. He made me sorry because he saw a sculpture in my apartment and said, “I want that.” It was quite a lot of money for those days, it was like 2,500 quid. Paul never asked the price until he decided to buy something. If he liked it, he wanted it.

Steven Gaines: I guess they didn’t have to think about the price

Robert Fraser: No, but most people, even if they don’t have to think about it, they want to know the price. Paul was very, very open-minded, but he was also more…Well, John was too, but I mean John was sort of very difficult to…He was more difficult to…He was very shy in a way, and it comes out in an aggressive way.

Steven Gaines: It’s an odd decision Paul made to live at his girlfriend’s home with her parents.

Robert Fraser: Paul was a very domestic sort of personality. He liked the idea.

Peter Brown: I didn’t think twice about it, but looking back on it now, it was pretty ahead of its time to move in with your girlfriend’s family.

Robert Fraser: Even now, he’s done exactly what he wants. He’s not really like…He never really lived a rock star’s life.

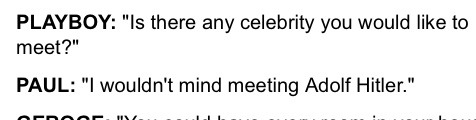

craziest beatle interview ive ever read (playboy)

thank you so much, I'll be sure to check them all out!!!! As for brazilian music, gosh, where to even start...

A very basic pick, but Chico Buarque is my absolute favorite, he's one of the greats of MPB for a reason. I love practically his entire discography, but his lyric writing is at its best on protest songs like Cálice, Cotidiano, and Roda-Viva. Here's Construção (1971) which gives me chills as much now as the first time I heard it.

Leci Brandão- Used her music to advocate for black/queer rights; some favorites are Antes Que Eu Volte a Ser Nada and Isso É Fundo de Quintal. Here's Deixa Pra Lá (1974)

Novos Baianos- A hugely influential band that mixed rock with samba, their sound is just so fun. Here's Mistério Do Planeta (1972)

Gal Costa- A beloved tropicália artist, her music is everything from beautiful to vibrant. Here's Baby (1969)

similarly with you I have no clue how well known their music is in other parts of latam LOL but I hope you enjoy :)

This is also why you won't see me posting about latin american bands like I do these four I'm too much of a mid century geek to get into anything later and if I think about my favourite latam bands or artists from the 60s/70s I start crying I need a certain degree of emotional separation

harry dubois would end death note in one episode. he'd be unkillable bc he has no fucking idea what his name is and then he'd go drink driving and accidentally run light over and the killings would mysteriously stop

in that mintz book does it mention the lost weekend story about off-his-head john yelling "this is all Roman Polanski's fault!!" while stabbing a mattress? Possibly from the same night as the chair tying. Ever since I read about that in May's book it's been my personal what happened in India - what do you MEAN, John????? Did he even know Polanski?

SCREAM no it does not but that beyond tracks 😭 it does however mention that he used to go to casinos and place chips on like almost every single number of the roulette wheel and he'd lose money bc it took more chips to do this than he'd make back when he inevitably won. and when mintz tried to explain this he just got confused bc "but I win every time". also they went to mcdonalds together once. and john thought he solved jfk's assassination (the driver turned around and did it, which. literal video of this not being true)

Hello!

I'm looking for a section of the lunchroom tape (from the Get Back sessions) where John says something to Paul along the lines of "I mean, you've only recently realised what you were doing to me". Does that ring any bells?

You seem to know your way around amoralto's archives, and I'm not having any luck searching there :)

Thanks!

Hi, @i-am-the-oyster (love the name, by the way)!

I think you might be referring to this section of the Lunchroom Tape:

JOHN: And it’s just that, you know. It’s only this year that you’ve suddenly realised, like who I am, or who he is, or anything like that.

I find this bit of the conversation particularly impenetrable; and all the more fascinating because of it. It's here that we have this famed exchange (whose full meaning still eludes me):

JOHN: Because you – ’cause you’ve suddenly got it all, you see. PAUL: Mm. JOHN: I know that, because of the way I am, like when we were in Mendips, like I said, “Do you like me?” or whatever it is. I’ve always – uh, played that one. PAUL: [laughs nervously] Yes. JOHN: So. PAUL: Uh, I’d been watching, I’d been watching. I’d been watching the picture. YOKO: Go back to George. What are we going to do about George?

I encourage folks to go listen to the full audio and transcript and try their hand at decoding it!

I don't know if it's accessible on the mobile app, but @amoralto has a separate page with links to all the Get Back excerpts, listed in chronological order. It's a pretty neat resource if you want to just binge through interesting little snippets from these sessions (some that made it onto the documentary, and many that didn't).

To those curious about the Lunchroom Tape in particular, here's a (play)list of all the transcribed excerpts, with @amoralto's descriptions for context:

We Have Egos

Over lunch, the remaining Beatles touch on George’s resignation from the band on the 10th, as well as a group meeting held the previous day which ended in less than desirable circumstances (with George leaving the room, frustrated by John’s persistently Yoko-filtered standard of communication). While Yoko contends that it would be easy for John (and Paul) to regain George’s favour, John points out that this is a more deeply-rooted issue than it may seem, compounded over the years by John and Paul’s treatment of George and his defaulted status within the group. Upon this problem of overriding egos, however, Paul suggests (passive-aggressively) that it isn’t just the Lennon-and-McCartney tandem that is causing George upset and consternation.

Jealousy For You

As the problem of George’s current resignation from the band is discussed, John makes it about him and Paul wonders what it’s all worth.

The Way We All Feel Guilty About Our Relationship To Each Other

John contends with how the force of his partnership with Paul and his relationship with Yoko has negatively affected George and perhaps directly contributed to George’s walkout on the group three days prior.

Cabbage

During a discussion on how the rest of the group should move forward after George’s departure on the 10th, John wonders if they should get George back at all, suggesting his role as a Beatle is replaceable (unlike his own or Paul’s), and likens this unkindly to how Ringo first replaced Pete Best. Paul notes that John has been the top buck in getting himself heard (and getting his way) since the inception of the group (which John protests) and quickly reassures Ringo when he wryly declares himself to be little more than rabbit food for the group. Paul admits that both he and John have done one over on George, albeit unconsciously as an effect of the competition and unaware of how it may have hurt George in the process, but John argues that he’s known since early childhood how manipulative he himself can be, and has tried to curb it to little avail.

What You Are

In the middle of a personal discussion with John and Ringo about the band, its tenuous future, and their relationships with one another, Paul (in response to John’s admission of insecurity in the face of external pressures from the public and media to perform) is emphatic about his faith in them and their abilities and contends that whatever interpersonal problems they have can be resolved, for what their music is worth.

Working At A Relationship

While Yoko and Paul conduct their own conversation with each other, Linda talks to John about the inevitable difficulties any relationship faces - even in the context of a musical partnership - and why it doesn’t prove the relationship itself is an expired one. John (inexplicably or not) laments that the White Album doesn’t sound like the genuine, inspired band collaboration they achieved in the past.

You've Got To Blame Yourself

As Paul encourages an unconfident Ringo to go ahead with his plans to record a solo LP, John hedgingly brings up his own apprehensions about following his instincts (especially when he’s not even sure what he really wants to do). In their inimitable and emotionally non-committal fashion, John and Paul engage in metaphors about intentions, conveying these intentions in actions, and how these actions may be conveyed by those who see it. (Basically: what John and Paul talk about when they talk about love.)

How Much More Have I Done Towards Helping You Write?

John and Paul have an obfuscating conversation about their songwriting partnership and creative process, which has been incapacitated by a lack of direction, misplaced (misread) intentions, and the unmet (unrealised) expectations they’ve inflicted upon each other. (In other words: issues. And some projecting of issues onto George, for good measure.)

What We're All About

In the midst of a personal discussion about working together within the band, John tries to explain the disconnect in their process, and why he can’t envision their songs the way Paul can. As both John and Paul circle around the issues of honest communication and (living up to) each other’s expectations, they eventually project onto George bring George into the quandary of the Lennon-McCartney partnership.

-

inearlynovember reblogged this · 1 week ago

inearlynovember reblogged this · 1 week ago -

inearlynovember liked this · 1 week ago

inearlynovember liked this · 1 week ago -

wordsinapapercup liked this · 3 weeks ago

wordsinapapercup liked this · 3 weeks ago -

dr-deathdefying liked this · 3 weeks ago

dr-deathdefying liked this · 3 weeks ago -

darkcat75 liked this · 1 month ago

darkcat75 liked this · 1 month ago -

etherealbrxt liked this · 1 month ago

etherealbrxt liked this · 1 month ago -

animaniacs16 liked this · 1 month ago

animaniacs16 liked this · 1 month ago -

insideoutworld liked this · 1 month ago

insideoutworld liked this · 1 month ago -

darkangelredmoon-blog liked this · 1 month ago

darkangelredmoon-blog liked this · 1 month ago -

alexschwrtz liked this · 1 month ago

alexschwrtz liked this · 1 month ago -

captnch4os liked this · 1 month ago

captnch4os liked this · 1 month ago -

peppecosefa liked this · 1 month ago

peppecosefa liked this · 1 month ago -

lanieie liked this · 1 month ago

lanieie liked this · 1 month ago -

y-yeehaw liked this · 1 month ago

y-yeehaw liked this · 1 month ago -

tangentnino liked this · 1 month ago

tangentnino liked this · 1 month ago -

lisaandthebeatles reblogged this · 1 month ago

lisaandthebeatles reblogged this · 1 month ago -

victorian-nymph reblogged this · 1 month ago

victorian-nymph reblogged this · 1 month ago -

zaladzoup liked this · 1 month ago

zaladzoup liked this · 1 month ago -

hermione-granger liked this · 2 months ago

hermione-granger liked this · 2 months ago -

mallowedheart liked this · 2 months ago

mallowedheart liked this · 2 months ago -

rhey-007 liked this · 2 months ago

rhey-007 liked this · 2 months ago -

metalupyour4ss liked this · 2 months ago

metalupyour4ss liked this · 2 months ago -

isaidilovedu2death liked this · 2 months ago

isaidilovedu2death liked this · 2 months ago -

yoludoca liked this · 2 months ago

yoludoca liked this · 2 months ago -

narcissus10191 liked this · 2 months ago

narcissus10191 liked this · 2 months ago -

here-am-i-sitting-in-a-tin-can reblogged this · 2 months ago

here-am-i-sitting-in-a-tin-can reblogged this · 2 months ago -

billgavemeextrachips reblogged this · 2 months ago

billgavemeextrachips reblogged this · 2 months ago -

billgavemeextrachips liked this · 2 months ago

billgavemeextrachips liked this · 2 months ago -

dontletmewaittoolong reblogged this · 2 months ago

dontletmewaittoolong reblogged this · 2 months ago -

fixxxd liked this · 2 months ago

fixxxd liked this · 2 months ago -

watermonstah reblogged this · 2 months ago

watermonstah reblogged this · 2 months ago -

starskytohutch liked this · 2 months ago

starskytohutch liked this · 2 months ago -

haritrash reblogged this · 2 months ago

haritrash reblogged this · 2 months ago -

juniorsailmakermattcruse reblogged this · 2 months ago

juniorsailmakermattcruse reblogged this · 2 months ago -

friendofgeorgeharrison reblogged this · 2 months ago

friendofgeorgeharrison reblogged this · 2 months ago -

impossiblecreations liked this · 2 months ago

impossiblecreations liked this · 2 months ago -

harrisons-hoe reblogged this · 2 months ago

harrisons-hoe reblogged this · 2 months ago -

shiniganmii liked this · 2 months ago

shiniganmii liked this · 2 months ago -

antipulgas reblogged this · 2 months ago

antipulgas reblogged this · 2 months ago -

anetsonet liked this · 2 months ago

anetsonet liked this · 2 months ago -

gilles-prost liked this · 2 months ago

gilles-prost liked this · 2 months ago -

hnneylix liked this · 2 months ago

hnneylix liked this · 2 months ago -

pushya448 liked this · 2 months ago

pushya448 liked this · 2 months ago -

cheese-danish-42 reblogged this · 2 months ago

cheese-danish-42 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

cheese-danish-42 liked this · 2 months ago

cheese-danish-42 liked this · 2 months ago -

hoodedandflying reblogged this · 2 months ago

hoodedandflying reblogged this · 2 months ago -

hoodedandflying liked this · 2 months ago

hoodedandflying liked this · 2 months ago -

twunkjohnlennon reblogged this · 2 months ago

twunkjohnlennon reblogged this · 2 months ago -

cr00kedloser liked this · 2 months ago

cr00kedloser liked this · 2 months ago

i mainly use twitter but their beatles fandom is nothing compared to this so here i am

111 posts