The Pinwheel Galaxy - This Giant Disk Of Stars, Dust And Gas Is 170,000 Light-years Across; Nearly Twice

The Pinwheel Galaxy - this giant disk of stars, dust and gas is 170,000 light-years across; nearly twice the diameter of the Milky Way. It is estimated to contain at least one trillion stars, approximately 100 billion of which could be like our Sun in terms of temperature and lifetime [6000x4690]

js

More Posts from Xnzda and Others

Tilt-shift photo of the space shuttle Endeavour by NASA

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/flyout/multimedia/endeavour/11-05-16-2.html

The Boomerang Nebula (Bow-tie Nebula)

The Boomerang Nebula is about 5000 light years away from the Earth, situated in the constellation Centaurus and is the coldest place known in the entire universe at a temperature of 1K. According to the astronomers, the nebula houses a central dying star which has been losing one-thousandth of a solar mass of material from the last 1500 years. The bow-tie shape of the nebula is said to have formed due to very fierce winds (blowing at about 500,000 kmph) blowing the ultra cold gas away from the dying star.

Image credit: Hubble/NASA/ESA

Cosmic rays

Cosmic rays provide one of our few direct samples of matter from outside the solar system. They are high energy particles that move through space at nearly the speed of light. Most cosmic rays are atomic nuclei stripped of their atoms with protons (hydrogen nuclei) being the most abundant type but nuclei of elements as heavy as lead have been measured. Within cosmic-rays however we also find other sub-atomic particles like neutrons electrons and neutrinos.

Since cosmic rays are charged – positively charged protons or nuclei, or negatively charged electrons – their paths through space can be deflected by magnetic fields (except for the highest energy cosmic rays). On their journey to Earth, the magnetic fields of the galaxy, the solar system, and the Earth scramble their flight paths so much that we can no longer know exactly where they came from. That means we have to determine where cosmic rays come from by indirect means.

Because cosmic rays carry electric charge, their direction changes as they travel through magnetic fields. By the time the particles reach us, their paths are completely scrambled, as shown by the blue path. We can’t trace them back to their sources. Light travels to us straight from their sources, as shown by the purple path.

One way we learn about cosmic rays is by studying their composition. What are they made of? What fraction are electrons? protons (often referred to as hydrogen nuclei)? helium nuclei? other nuclei from elements on the periodic table? Measuring the quantity of each different element is relatively easy, since the different charges of each nucleus give very different signatures. Harder to measure, but a better fingerprint, is the isotopic composition (nuclei of the same element but with different numbers of neutrons). To tell the isotopes apart involves, in effect, weighing each atomic nucleus that enters the cosmic ray detector.

All of the natural elements in the periodic table are present in cosmic rays. This includes elements lighter than iron, which are produced in stars, and heavier elements that are produced in violent conditions, such as a supernova at the end of a massive star’s life.

Detailed differences in their abundances can tell us about cosmic ray sources and their trip through the galaxy. About 90% of the cosmic ray nuclei are hydrogen (protons), about 9% are helium (alpha particles), and all of the rest of the elements make up only 1%. Even in this one percent there are very rare elements and isotopes. Elements heavier than iron are significantly more rare in the cosmic-ray flux but measuring them yields critical information to understand the source material and acceleration of cosmic rays.

Even if we can’t trace cosmic rays directly to a source, they can still tell us about cosmic objects. Most galactic cosmic rays are probably accelerated in the blast waves of supernova remnants. The remnants of the explosions – expanding clouds of gas and magnetic field – can last for thousands of years, and this is where cosmic rays are accelerated. Bouncing back and forth in the magnetic field of the remnant randomly lets some of the particles gain energy, and become cosmic rays. Eventually they build up enough speed that the remnant can no longer contain them, and they escape into the galaxy.

Cosmic rays accelerated in supernova remnants can only reach a certain maximum energy, which depends on the size of the acceleration region and the magnetic field strength. However, cosmic rays have been observed at much higher energies than supernova remnants can generate, and where these ultra-high-energies come from is an open big question in astronomy. Perhaps they come from outside the galaxy, from active galactic nuclei, quasars or gamma ray bursts.

Or perhaps they’re the signature of some exotic new physics: superstrings, exotic dark matter, strongly-interacting neutrinos, or topological defects in the very structure of the universe. Questions like these tie cosmic-ray astrophysics to basic particle physics and the fundamental nature of the universe. (source)

The only home we’ve ever known. Clouds and sunlight over the Indian Ocean, as seen from Discovery during the STS-96 mission in 1999.

Dust, stars, and cosmic rays swirling around Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, captured by the Rosetta probe. (Source)

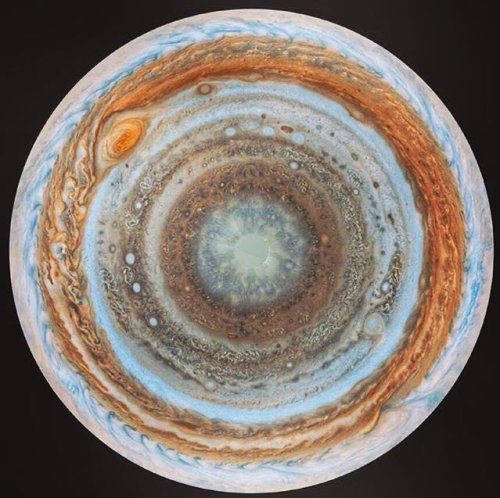

What is it Like to Visit Jupiter?

Jupiter is the largest planet in our solar system. For some perspective, if it were hollow, more than 1,300 Earths could fit inside of it! The giant planet contains two-thirds of all the planetary mass in the solar system and holds more than dozens of moons in its gravitational grip. But what about a visit to this giant planet?

Let’s be honest…Jupiter is not a nice place to visit. It’s a giant ball of gas and there’s nowhere to land. Any spacecraft – or person – passing through the colorful clouds gets crushed and melted. On Jupiter, the pressure is so strong it squishes gas into liquid. Its atmosphere can crush a metal spaceship like a paper cup.

Jupiter’s stripes and swirls are cold, windy clouds of ammonia and water. Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is a giant storm BIGGER THAN EARTH! This storm has lasted hundreds of years.

Since Jupiter’s atmosphere is made up of mostly hydrogen and helium, it’s poisonous. There’s also dangerous radiation, more than 1,000 times the lethal level for a human.

Scientists think that Jupiter’s core may be a thick, super hot soup…up to 50,000 degrees! Woah!

The Moons

Did you know that Jupiter has its own “mini solar system” of 50 moons? Scientists are most interested in the Galilean satellites – which are the four largest moons discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610.

Today, Galileo would be astounded to know some of the facts about these moons. The moon Io has active volcanos. Ganymede has its own magnetic field while Europa has a frozen crust with liquid-water underneath making it a tempting place to explore for future missions.

When Juno arrives to Jupiter on July 4, it will bring with it a slew of instruments such as infrared imager/spectrometer and vector magnetometer among the half a dozen other scientific tools in its payload.

Juno will avoid Jupiter’s highest radiation regions by approaching over the north, dropping to an altitude below the planet’s radiation belts – which are analogous to Earth’s Van Allen belts, but far more deadly – and then exiting over the south. To protect sensitive spacecraft electronics, Juno will carry the first radiation shielded electronics vault, a critical feature for enabling sustained exploration in such a heavy radiation environment.

Follow our Juno mission on the web, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Tumblr.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

-

daemondamian liked this · 6 years ago

daemondamian liked this · 6 years ago -

eastern-wind liked this · 6 years ago

eastern-wind liked this · 6 years ago -

tomoe1235 liked this · 6 years ago

tomoe1235 liked this · 6 years ago -

lshaffery liked this · 6 years ago

lshaffery liked this · 6 years ago -

notisaidthechicken liked this · 6 years ago

notisaidthechicken liked this · 6 years ago -

jeebssred liked this · 6 years ago

jeebssred liked this · 6 years ago -

metalzoic liked this · 6 years ago

metalzoic liked this · 6 years ago -

dancewiththedevil101 liked this · 6 years ago

dancewiththedevil101 liked this · 6 years ago -

fagdykefrank liked this · 6 years ago

fagdykefrank liked this · 6 years ago -

smallfryingpan liked this · 6 years ago

smallfryingpan liked this · 6 years ago -

kotakarts liked this · 6 years ago

kotakarts liked this · 6 years ago -

ifjgh liked this · 6 years ago

ifjgh liked this · 6 years ago -

elchivo72 reblogged this · 6 years ago

elchivo72 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

elchivo72 liked this · 6 years ago

elchivo72 liked this · 6 years ago -

giorgioooo-blog1 liked this · 6 years ago

giorgioooo-blog1 liked this · 6 years ago -

scootis-the-scoot liked this · 6 years ago

scootis-the-scoot liked this · 6 years ago -

therodentqueen liked this · 6 years ago

therodentqueen liked this · 6 years ago -

ajc18615425 liked this · 6 years ago

ajc18615425 liked this · 6 years ago -

asoftlittlekitten reblogged this · 6 years ago

asoftlittlekitten reblogged this · 6 years ago -

asoftlittlekitten liked this · 6 years ago

asoftlittlekitten liked this · 6 years ago -

i-s-d-m-8 liked this · 6 years ago

i-s-d-m-8 liked this · 6 years ago -

jester-toon-rabbit liked this · 6 years ago

jester-toon-rabbit liked this · 6 years ago -

dopeoperafriendweasel liked this · 6 years ago

dopeoperafriendweasel liked this · 6 years ago -

arkang3lsworld liked this · 6 years ago

arkang3lsworld liked this · 6 years ago -

xnzda reblogged this · 6 years ago

xnzda reblogged this · 6 years ago -

deannasaults199328 liked this · 6 years ago

deannasaults199328 liked this · 6 years ago -

knifeybunny reblogged this · 7 years ago

knifeybunny reblogged this · 7 years ago -

ineedspacex-blog reblogged this · 9 years ago

ineedspacex-blog reblogged this · 9 years ago -

actualshootingstar reblogged this · 9 years ago

actualshootingstar reblogged this · 9 years ago -

robotsreferenceblog reblogged this · 9 years ago

robotsreferenceblog reblogged this · 9 years ago -

pinche--pendeja reblogged this · 9 years ago

pinche--pendeja reblogged this · 9 years ago -

antaaresa reblogged this · 9 years ago

antaaresa reblogged this · 9 years ago -

doremirocker liked this · 9 years ago

doremirocker liked this · 9 years ago -

10383c reblogged this · 9 years ago

10383c reblogged this · 9 years ago -

fluffysheepgirl reblogged this · 9 years ago

fluffysheepgirl reblogged this · 9 years ago -

rdanieel liked this · 9 years ago

rdanieel liked this · 9 years ago -

rdanieel reblogged this · 9 years ago

rdanieel reblogged this · 9 years ago -

lil-bobaggins reblogged this · 9 years ago

lil-bobaggins reblogged this · 9 years ago